Season 1: Episode 2

The Red Man Was Pressed

How did we go from more than 50 million wild bison in the United States to just 23 free-roaming animals today? And how does the decimation of the herds relate to the oppression of Native Americans?

Read More

CSKT Timeline

Here's a link to the timeline Germaine White refers to in this episode, created by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and shared here with their permission.

Buffalo in Indian Country

These are just a few of the many tribes and other groups working to help rebuild the connections between bison and Native Americans:

Audio Extra

Video Extras

Credits

Threshold is produced by me, Amy Martin, with help from Nick Mott, Zoe Rom, Jackson Barnett, Nora Saks and Josh Burnham. Special thanks to Michael Wright, Ross Taylor, and Michael Connor for their help on this episode. Music recorded at the Kyi-Yo Pow-Wow was used with permission of the pow-wow organizers. All of the rest of the music was by Travis Yost.

Transcript

[00:00] INTRODUCTION

AMY: Whatever you’re doing, stop. Just for a second.

SOUND: STREET NOISES

AMY: Look out the window. Imagine there’s a huge, brown, shaggy animal looking back at you. With horns. It’s standing there in your backyard, or in the parking lot of your office building.

SOUND: KIDS PLAYING

AMY: It’s wandering across that field, that highway, that playground. It’s browsing on the little patch of grass between the strip mall and the gas station.

SOUND: TRUCK GOING BY, HONKING

AMY: It’s trotting down your quiet suburban street.

SOUND: BISON TROTTING BY ON YNP ROAD

AMY: That creature in your backyard? It’s an American bison. Also called buffalo. Six feet tall, up to 2,000 pounds. Our national mammal.

KEITH: George Washington shot a buffalo in Virginia.

AMY: Welcome to Threshold. I’m Amy Martin, and this is Keith Aune.

KEITH: Yeah, ah, my name is Keith Aune. That’s spelled A – U – N – E. And I am the director of bison programs for the Wildlife Conservation Society.

AMY: And Keith says that almost without exception, wherever you are in the United States, bison used to live there too.

KEITH: They occurred from Virginia to the California, nearly the California coast.

AMY: We think of buffalo as a western animal, but they belong in Massachusetts and New York as much as they do in Wyoming and Montana, where I live.

KEITH: Daniel Boone and all of his wanderings around – we think he found trails and made trails? He didn’t make trails, he followed buffalo traces. They’re well-known traces. They were Indian and buffalo trails that went through the forest and the woodlands.

AMY: Picture them drinking from the Trinity River in downtown Dallas, courting each other on State Street in Chicago, or giving birth to their calves in Freedom Park in Atlanta.

KEITH: They occurred from the Chihuahuan Desert in Mexico – northern Mexico had lots of bison – all the way to central Alaska. They didn’t really like coastal areas...

AMY: But, just go a few miles inland...

KEITH: ... and you would find them in meadows and grasslands. And people don’t realize – mariners saw them off the coast of Florida when they were sailing around, you know, the Gulf Coast. Gulf Coast tribes in Texas, Louisiana, and Florida would sometimes go inland and hunt buffalo. They wouldn’t have to go all that far, especially in Texas. And you go east, there’s buffalo names everywhere in the east. Why is that? Well, because there was buffalo.

AMY: There’s a Buffalo, Ohio. Buffalo, Wisconsin. Buffalo, West Virginia...

KEITH: ...Kansas, Illinois, Indiana – just filled with buffalo, tremendous tall-grass prairies, really rich in grass...

AMY: Everything you think of as your territory – your house, your kids’ school, your place of work, and the roads that connect them all? That’s bison territory too.

KEITH: There’s stories all along the way.

MUSIC

AMY: Humans first encountered bison around 75,000 years ago, on our great migration out of Africa. Somewhere north of Turkey we probably happened upon bison for the first time. We quickly learned how to hunt them, and from the artwork left behind on cave walls, we can tell they became incredibly important. We made images of bison before we made images of ourselves. Along with the horse, we painted them more than any other animal. We even engraved their images onto little pebbles and bones, so we could carry them with us as we spread out across Europe and Asia. They were with us on the long trek east through Siberia at the end of the last Ice Age. In fact, they crossed over the Bering Land Bridge into North America hundreds of thousands of years before we did – who knows, they may have inspired us to make that crossing ourselves. So when you think about this long history we’ve had with this animal, our current, mostly bison-free existence starts to look like an anomaly.

FADE MUSIC

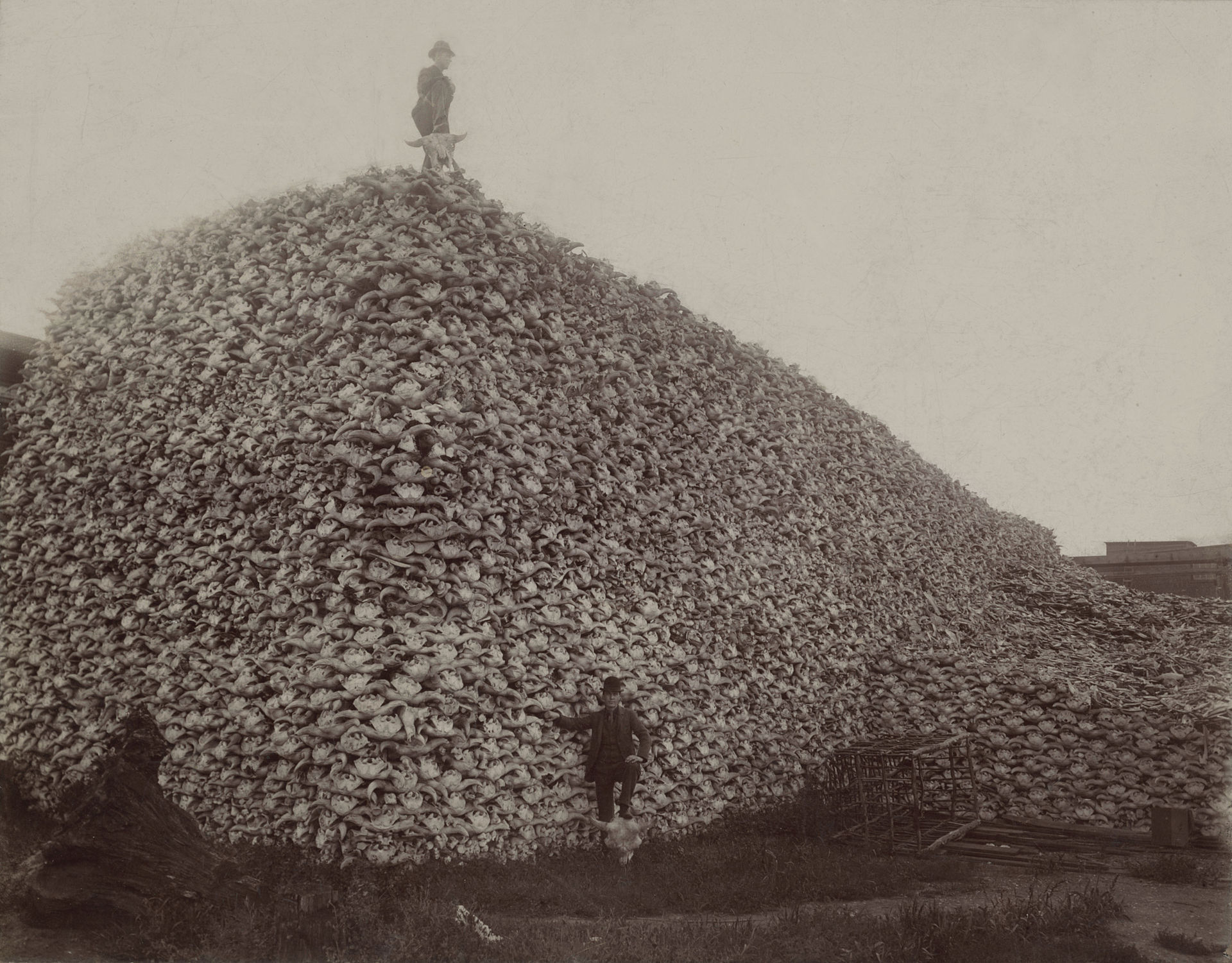

AMY: In our last episode we introduced two numbers: 50 million wild bison before Europeans arrived in North America, 23 wild bison in the United States in 1901. This time we’re going to try and fill the gap in between – how did we go from such abundance to such scarcity in such a short time? Well, like almost everything...it’s complicated.

MUSIC: THRESHOLD THEME

“You know the buffalo took care of us in our past and in this day and age they can take care of us in a new way.”

“They’ve always been like a very spiritual, very important animal.”

“They’re not willing to take the hard step. Knock that herd down to the proper size.”

“I feel like they’re banking on the ignorance of the American population about American Indian people.”

“Maybe they don’t even understand agriculture.”

“We came very very close to losing them, it’s almost a miracle we did not.”

“This is the way it’s supposed to be. They were here first.”

[04:38] SEGMENT A

SOUND: BIRDS CHIRPING

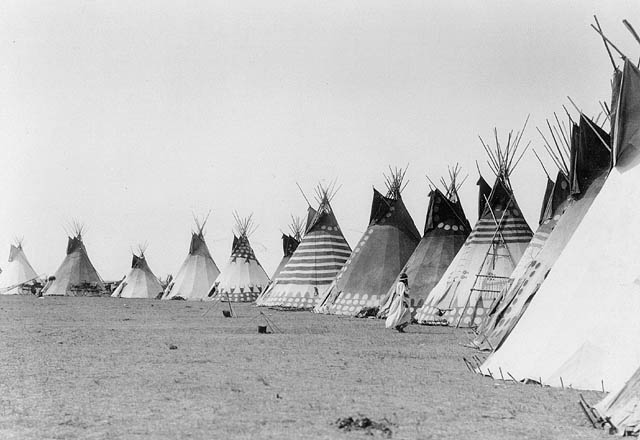

GERMAINE: Bison were at the very heart of our traditional way of life.

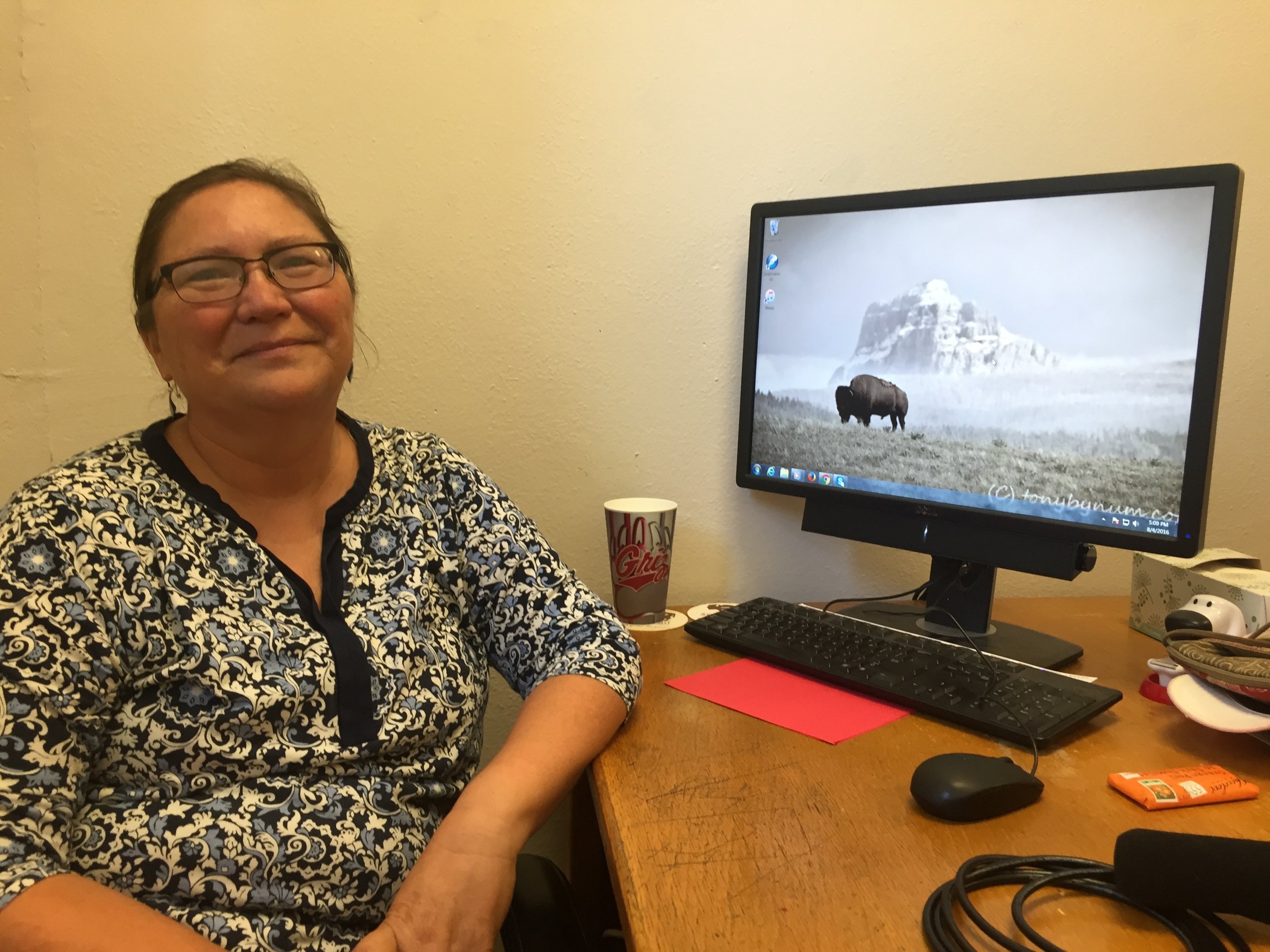

AMY: This is Germaine White.

GERMAINE: For years we hunted bison, lived in relationship with bison...and they provided for not just our material needs -- our shelter, our clothing, our food – but also provided for our spiritual needs as well.

AMY: Germaine is a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in northwest Montana. She’s their information and education specialist. And she’s trying to explain some pretty fascinating stuff about the word “bison” in Salish. First of all, there’s just the way it’s pronounced –

GERMAINE: quee-quai

AMY: OK, let me try that. Quee-quai. No, that’s not it. Can I hear that again?

GERMAINE: quee-quai

AMY: Yeah. I’m just really not pulling that off. So moving on to the other cool thing about this word – it contains multitudes. The literal translation of it is “many little black spots.”

GERMAINE: When they looked out across the landscape there was such an abundance of black spots forever.

AMY: So the very word means abundance…

GERMAINE: Many, little blacks, yes, many...

AMY: So, in Salish, the concept of what a bison is includes the idea of “a lot.” And that makes sense – bison had outnumbered humans on the planet for millennia. The idea that this could be flipped, and that we could outnumber them, that would have seemed crazy to Germaine’s family, even just a couple of hundred years ago.

GERMAINE: So. Our place on this landscape, and our culture, has this extraordinary time depth...

AMY: Germaine says her tribes have been living in this region for around 12,000 years. They created a timeline to try to visualize that history.

GERMAINE: And they have taken that twelve thousand years and wrapped it around a twenty-four-hour clock. And what that shows is that Lewis and Clark arrived at about eleven twenty seven p.m. – about a half hour before midnight.

AMY: So, everything from the Declaration of Independence to the last election is just a tiny sliver of Native American history.

MUSIC

AMY: And now, try to put that history on the bison’s timeline. They’ve been in North America for hundreds of thousands of years. That means the majority of their time on this continent there were no pesky two-legged, tool-making hunters to worry about – no humans at all. And this last 240 years that we call American history? That’s just a blink of a big brown buffalo eye.

GERMAINE: The elders never imagined that there would be a time that there were not bison here for us.

AMY: But the unimaginable was about to become reality.

MUSIC

ROBERT: It did not start as an intentional extermination of the bison…

AMY: This is Robert Chester.

ROBERT: but it certainly became far more systematic effort to do just that over time.

AMY: Robert says that as Europeans began to arrive, bison were hunted out in waves, region by region. First the northeast, then the southeast, then the mid-west. At the same time, the introduction of the horse radically changed Native American hunting practices and disturbed the ancient balance between people and buffalo. So by the early 1800s, bison in the lower 48 were divided into two areas – the northern and southern plains, west of the Mississippi. Then the cattle kingdom exploded in Texas, and the southern herds were hit hard.

ROBERT: Everything kind of came to a head by the 1840s and 1850s so that you had in some years it was difficult increasingly especially in dry years to find bison, you had people who were actually starving.

AMY: The 1860s brought huge changes that ricocheted across the country. The Homestead Act, the Civil War, completion of the transcontinental railroad. The nation was turning its gaze westward. In the 1870s, the southern herds were largely hunted out, and there was just one part of the country where the bison – and the people who depended on them – had any hope of resistance left. The northern plains.

MUSIC

AMY: The federal government was finding it very difficult to subdue the people who lived in the vast, wind-swept grasslands of Montana, Wyoming and the Dakotas.

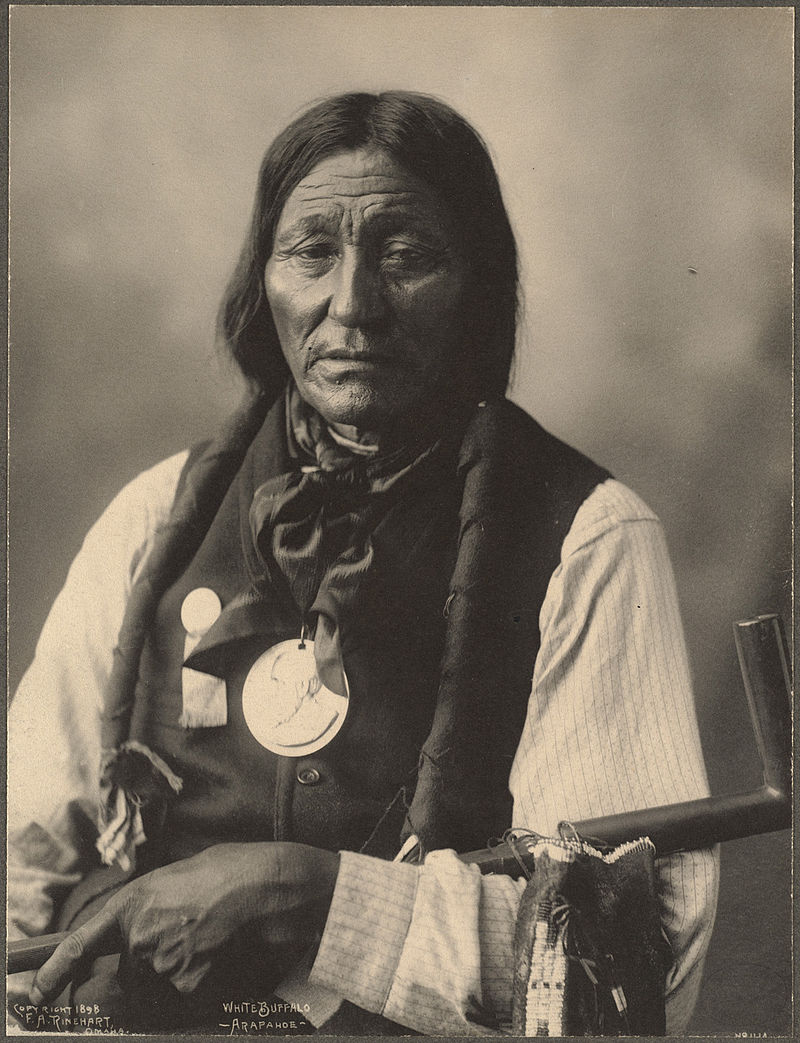

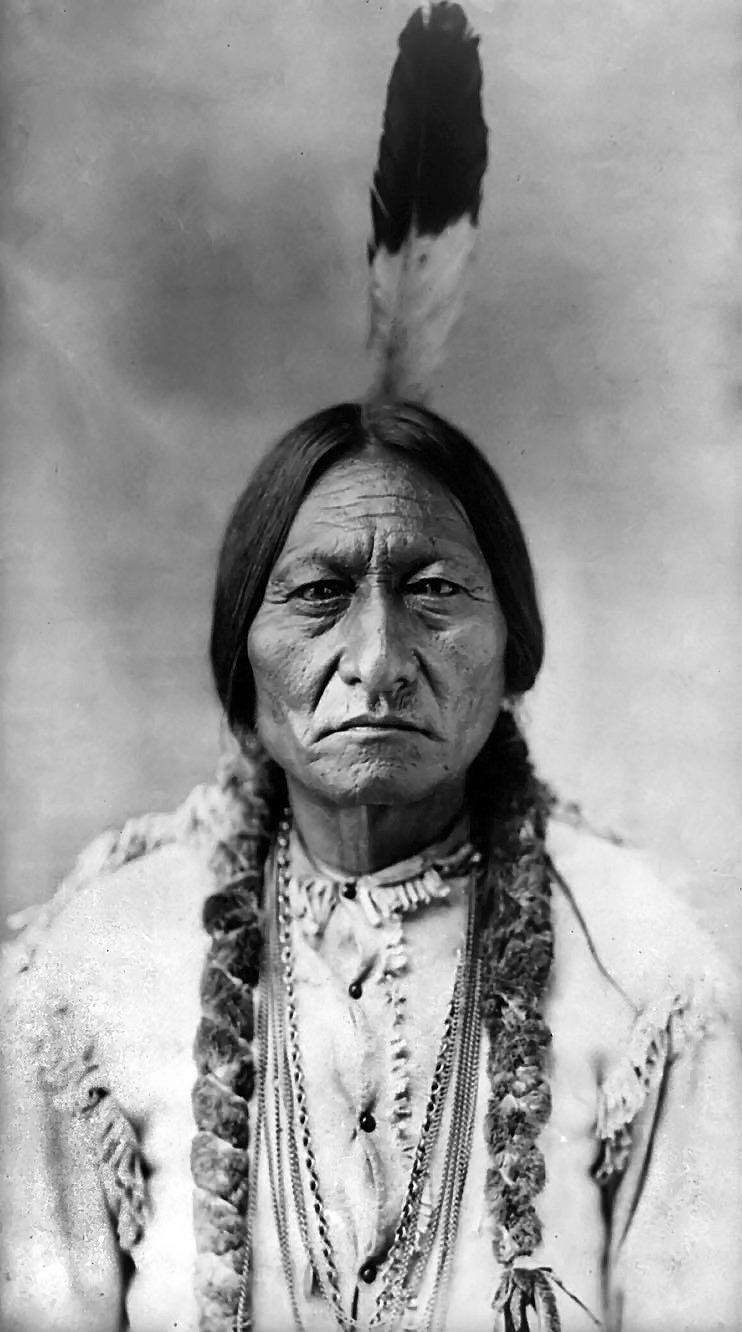

ROBERT: You have one of the finest cavalries in the history of the world – the Sioux the Cheyenne, the Arapaho, the Crow – you know these people lived on horseback. So it's very hard to defeat them decisively. And there's all this space. I mean it's not like you know, you're socking it out in the trenches, you know.

AMY: It was more like guerrilla warfare. Unpredictable and confusing. These tribes knew this vast landscape intimately. They traveled light, moved fast, and often outwitted the Army despite the fact that the federal government had more and better guns.

ROBERT: As long as the bison herds are there – even if it's becoming increasingly untenable to oppose the U.S. military – at least there is that temptation to try.

AMY: One Army officer was quoted as saying, “Only when the Indian becomes absolutely dependent on us for his every need, will we be able to handle him. He's too independent with the buffalo. But if we kill the buffalo we conquer the Indian.” This idea took hold. Maybe the most effective way to break the spirit of resistance in Indian people was to exterminate the bison.

ROBERT: It may not be official policy, but everything the United States Army and the federal government is doing seems to suggest that it is official policy even if they're not coming out and saying that it is.

AMY: And sometimes they did come out and say it. In his memoirs, General John M. Schofield wrote, "I wanted no other occupation in life than to ward off the savage and kill off his food until there should no longer be an Indian frontier in our beautiful country." And then there’s General Tecumseh Sherman – author of the “scorched earth” strategy in the Civil War. Here’s an excerpt from an 1869 issue of the Army Navy Journal: "General Sherman remarked in conversation the other day that the quickest way to compel the Indians to settle down to civilized life was...to shoot buffaloes until they became too scarce to support the redskins."

MUSIC

AMY: And that’s essentially what happened. Some Army leaders used bison for target practice, or set up contest among soldiers to see who could kill the most bison in a day. But these sorts of things were really just the tip of the iceberg. Because as new railroads were built through the heart of the remaining bison territory, they brought something neither the animals nor the Native Americans had ever seen before – men who slaughtered buffalo not to feed humans, but to feed machines.

SOUND: TRAIN WHISTLE

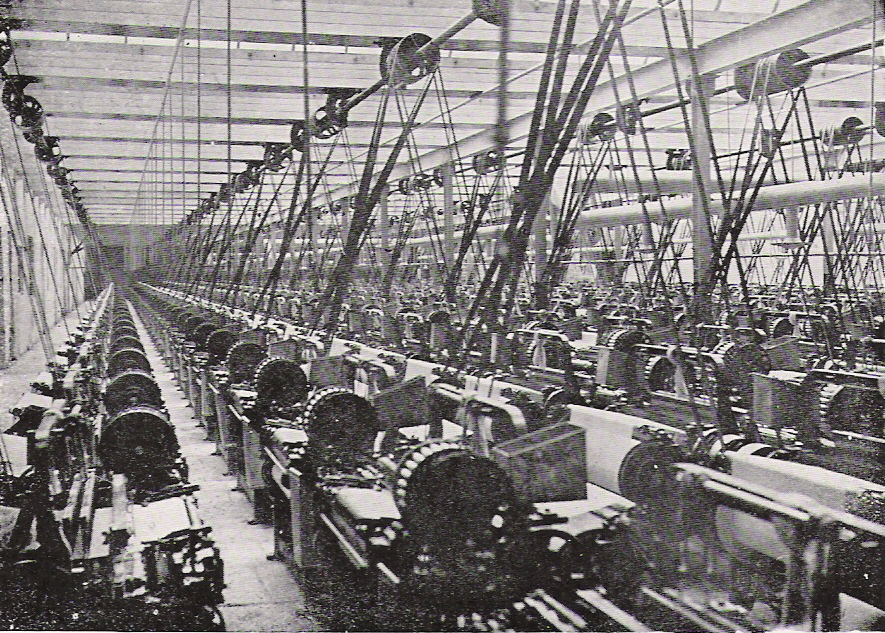

ROBERT: Bison hides make really good leather for belting, which is used in factories in the northeast.

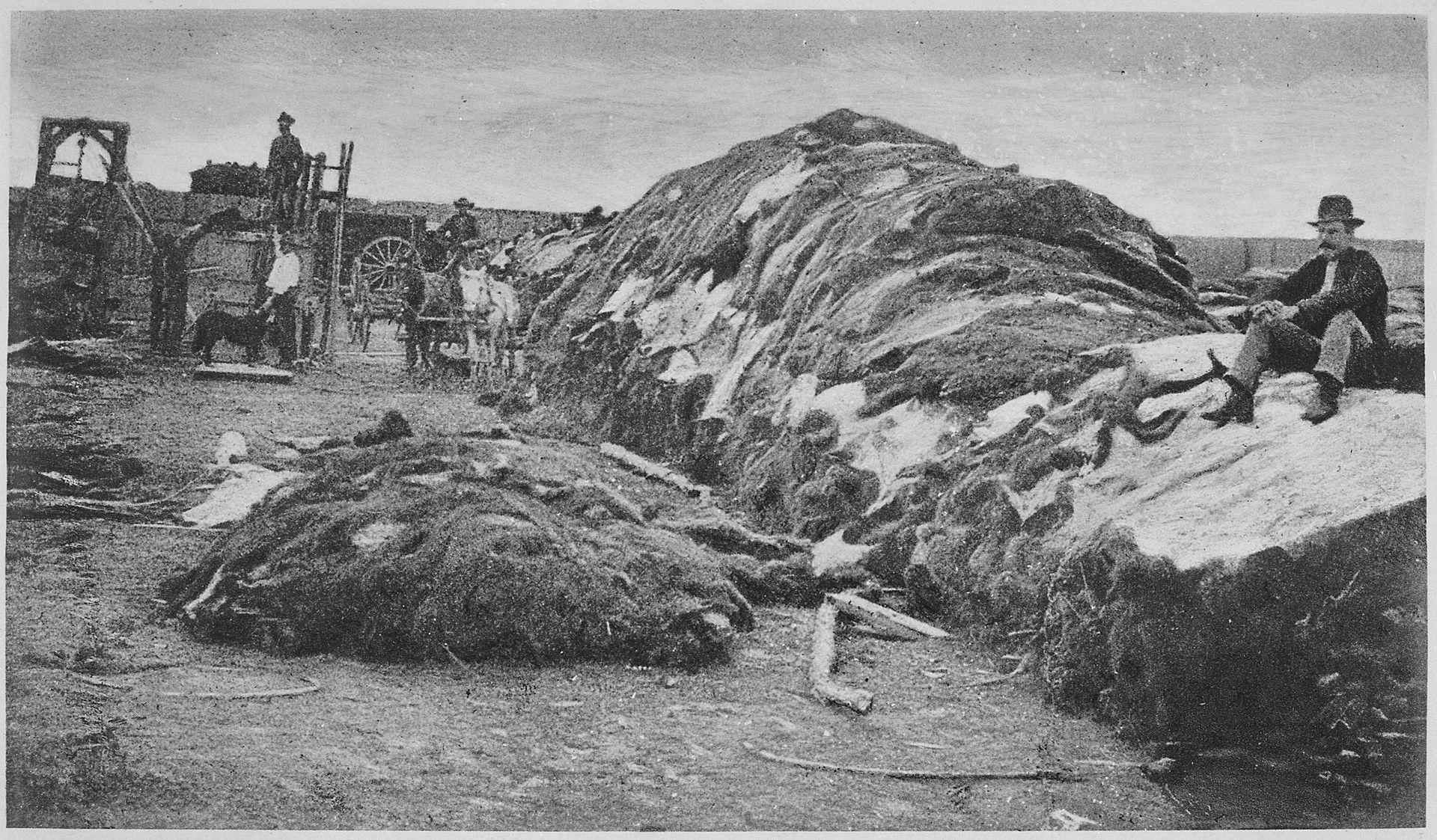

AMY: They were called hide hunters, and at their peak, they shot thousands of buffalo every day. They sold the hides for around three dollars a piece, and shipped them back east, where they were used to run the machinery powering the Industrial Revolution.

ROBERT: They typically were not eating the meat. Most of the meat was left to rot.

AMY: You kill the bison, you get the hide off of it and you move on to the next –

ROBERT: And often you take the tongue. Because the tongue was a delicacy. And then also eventually their skulls will be ground up and sent back east to make fertilizer with as well.

AMY: For tens of thousands of years, bison hunting had been limited by what people could process, carry and consume. Now, it was limited by a burgeoning industrial economy. Which is to say, there were virtually no limits at all.

SOUND: TRAIN

ROBERT: I mean and you know probably as well they had guns mounted on trains so that tourists could shoot at bison as they went by. And so in addition to the hide hunters actually taking the hides you had people simply shooting bison as a rite of passage as they went west on a train as a source of amusement and entertainment.

AMY: I didn’t know this until Robert told me, and honestly it’s one of the things that I learned in my reporting for this series that has troubled me the most. The idea of shooting and most likely wounding animals – not because you need the meat, not even to make some money off the hide, but just for fun? I just find that deeply disturbing. And Robert says it disturbed many people at the time as well. Leaders of all sorts of Native American tribes protested the slaughter, both for the buffalo’s sake and for the sake of their own communities. And many Army officers actually argued against it too. Some said it was cruel, others said it was a waste of god’s creation, and some claimed it was just not a good strategy, because it made Native people more hostile than they would have been otherwise. Eventually even Congress got involved.

ROBERT: There's a bill that's put through Congress and then is passed and reaches President Grant’s desk. And he vetoes it.

AMY: So the bill failed. But it’s noteworthy that it almost became law. It shows that America wasn’t of one mind then any more than it is now. It’s not that there was no protest against the bison slaughter. It’s just wasn’t strong enough.

MUSIC

AMY: In just one winter – the winter of 1872 to ‘73 – more than one-and-a-half million bison were killed. Meat was left to rot on the ground and Indian people starved.

MUSIC

AMY: We’ll have more after this short break.

Break

[15:14] SEGMENT B

AMY: Welcome back to Threshold, I’m Amy Martin, and before the break we were in the year 1872. And we’re going to hone in on that one year for just a few minutes, because it turns out two bison-related American icons were created that year. Can you guess?

MUSIC

AMY: I’ll give you the easiest one first. 1872 is the year Yellowstone National Park was founded – the world’s first national park, and ultimately the place where bison were saved from extinction. The other thing might be harder to guess. So here’s a clue:

MUSIC:

“Oh give me a home where the buffalo roam”

AMY: That’s right. “Home On the Range.”

MUSIC:

“Where the deer and the antelope play

where seldom is heard, a discouraging word

and the skies aren’t cloudy all day”

AMY: “Home On the Range” began as a poem written by a Kansas doctor named Brewster Higley in 1872. It became a popular campfire song, and in the great folk tradition, lots of people added verses, changed lines, and made the song their own. And that’s part of what makes it so interesting to me – it’s not just one person’s perspective. It’s a window into the mindset of a whole group of people from the late 19th century.

MUSIC:

“Home, home on the range”

AMY: One of the primary emotions in “Home On the Range” is nostalgia – it sounds like it was written by someone looking back at changes that happened long before. But actually, Higley was mourning the loss of the buffalo before the destruction reached its peak. An average of 5,000 bison were killed every day in 1872, and the two following years. So if we’d really wanted a home where the buffalo roamed, 1872 would have been a great year to do something about it. And then, there’s this verse:

MUSIC:

“The Red man was pressed from this part of the west

It’s not likely he’ll ever return

To the banks of the Red River where seldom if ever

His flickering campfire still burns”

AMY: Higley didn’t write these lines – who don’t know exactly who did – but it’s definitely a continuation of this impulse to preemptively eulogize a loss rather than acting to prevent it. In 1872, the Sand Creek Massacre was a very recent memory, and the massacre at Wounded Knee was still 18 years away. So this verse waxes nostalgic about the loss of the Indians while they are being actively persecuted. Maybe it was an attempt to call attention to that persecution, to voice dissent. But if so, it’s a very passive sort of protest – they say, “the Red man was pressed” – but ...pressed by whom? There’s no responsibility assigned. Or taken.

ROBERT: The term vanishing is a very important term because simultaneously people are referring to vanishing wildlife and the vanishing race which is Native Americans.

AMY: Once again, historian Robert Chester. And he says this word “vanishing” shows up a lot in the late 1800s. It’s another passive-voice term, it leaves the agents of the destruction unnamed. These people, these bison, they’re just...vanishing.

ROBERT: There’s fatalism. Fatalism is important in understanding how people are thinking about the future fate of -- or destiny of -- these people, and of these animals that they're vanishing which it implies that they will be gone. They will go extinct. Whether they are people or they are animals. There is no longer that many of them left and they're making their exit.

AMY: Is it fair to say that people were saying the destruction of Native Americans and the destruction of bison was inevitable long before it was necessarily inevitable? I mean was that an argument that was used to create that reality?

ROBERT: Yeah, yeah, actually, yeah. It's important to understand that some people are more ambivalent than others. That's really important because some people are saying oh this is this is sad, this is tragic, we should try to do something to save some of this. And other people are saying well no, we shouldn't be sad about this because this is what happens with progress.

AMY: This is the doctrine of Manifest Destiny – an assumption that Euro-American culture was destined to reign supreme. This proved to be an incredibly powerful way to ignore the rights of Native Americans. Just declare them prematurely extinct. Write them out of existence in your head before you try to wipe them out on the ground. Because once the destruction of a group of people – or a species of animals – is declared inevitable, then we don’t have to think about what we’re doing. It’s just happening, and we’re free to feel sad about it without taking any responsibility.

MUSIC:

“where the skies are not cloudy all day…”

AMY: History is full of contradictions. Some Native Americans engaged in the hide trade. Some Army soldiers became protectors of the Yellowstone bison. And we ended up saving the buffalo on land that was more or less stolen from tribal people. But when we zoom out and think on the bison’s timeline, the essence of the story comes into sharp relief. For more than half-a-million years, bison filled the continent. And then, in a couple of hundred years, they were nearly exterminated. From this angle, the bison slaughter doesn’t look inevitable, it looks like an aberration – a dramatic departure from the norm. And it didn’t happen by accident. It was – at least in part – the result of choices people made. Choices that could have gone another way.

MUSIC

AMY: Some bison were allowed to live as livestock – they were interbred with cattle, and confined behind fences. And some Native Americans were allowed to live, if they agreed to give up their cultures and their livelihoods, and adopt European-American ways.

ROBERT: You do have this very disturbing and eerie parallel going on in terms of the herding up of Indians and the herding up of bison.

AMY: Chief Plenty Coups of the Crow said, “When the buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened. There was little singing anywhere.”

MUSIC

AMY: It wasn’t just the bison population that dropped dramatically in the 19th century – the number of indigenous people in the country plummeted too. In his book, Blood Struggle, Charles Wilkinson says that at the turn the century, there were only about 250,000 Native people in the United States – a 95% reduction in their numbers. Disease was the number one killer, but it was a many-pronged assault of war, displacement, starvation and other factors. And as it was happening, many Americans told themselves this story of Manifest Destiny – this belief that the annihilation of Native Americans was certain and that their only path forward was to surrender everything that made them strong.

FADE MUSIC

AMY: But, as it turns out, the fatalists were wrong.

SHORT MUSIC SWELL

AMY: Because despite the brutality against bison and indigenous people, both survived.

SOUND: Knocking on a door

AMBI: Hello...

AMY: Rosalyn LaPier greets me with a big smile from behind a maze of shelves full of glass jars. Each jar contains a plant, labeled in both Latin and Blackfeet. And they tell a different sort of story.

AMBI: …I just brought back all my specimens…

AMY: Rosalyn’s an environmental historian at the University of Montana. She’s also a member of the Blackfeet Tribe and the Red River Metis. And these plants specimens she’s collected are one of the many ways Blackfeet people are keeping their culture alive.

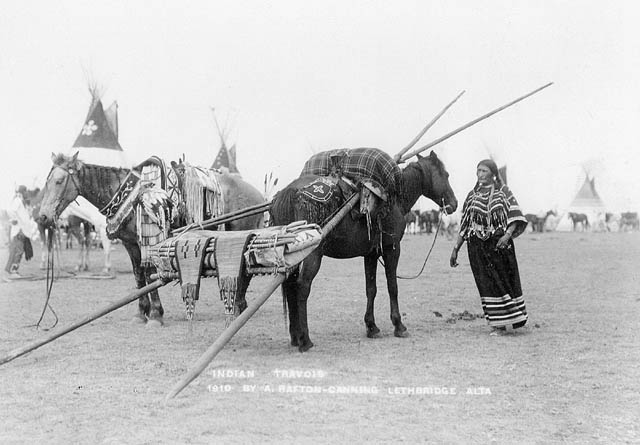

ROSALYN: The Blackfeet probably traveled between 12 and 14 different places in the summertime.

AMY: Before the reservation era, the Blackfeet had been a semi-nomadic tribe. But Rosalyn says that word – nomadic – is misleading, because it calls to mind a sort of aimless wandering. And that’s not at all how it was.

ROSALYN: Each place that they went to they went specifically for gathering resources. Whether it was hunting or whether it was gathering berries or whether it was gathering medicine or whether it was for religious purposes. They were moving to very specific places.

AMY: This movement was the key to survival not only for people, but for bison, too. In fact, roaming buffalo helped make this ecosystem what it was. They would graze heavily in one area for a little while, and then they move on, while that spot recovered. And all sorts of birds, small mammals, amphibians and insects followed in their wake – they evolved to time their life cycles to the movements of the herds. Bison are sometimes called the “engineers of the prairie” because of the way their behaviors affected the whole system. And Rosalyn says the Blackfeet were not only careful observers of all of these relationships. They were doing plenty of engineering themselves.

ROSALYN: There's kind of a stereotype that Native people followed the bison, right. That they would just kind of willy-nilly wherever the bison were that they would follow them. In reality, what research is beginning to show is that Native people created places where the bison would come to them.

AMY: One of the ways they did this was through fire.

ROSALYN: So for example bison don't like fire or the smell of smoke. So if you're burning something over here then the bison are going to be moving away from that. So that's kind of a push method.

AMY: And they used fire to pull bison into certain areas as well.

ROSALYN: So if you fire an area the next year the grass is going to be greener. So the bison will come back because they want to eat the grass.

AMY: This is partly why reservation life was so disruptive – the Blackfeet didn’t think of “home” as one particular dot on a map. It was a region, a set of places. And survival depended on movements between them. And it worked. For the people, the animals and the plants. For millennia. But the European-Americans arrived and declared it all backward and wrong. They ignored Indian expertise and pushed them to become farmers. Many homesteaders soon found out just how hard it was to raise crops and cattle on this harsh, dry land, but that didn’t seem to shake anyone’s convictions. Farming and ranching were considered morally superior to Native people’s practices, no matter what the conditions on the ground suggested.

MUSIC

GERMAINE: The elders’ lament is that our children are like buffalo born behind a fence. They don't know the extent of our aboriginal territory. Many of them don't know the great time depth of our relationship with this place.

AMY: Again, this is Germaine White from the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

GERMAINE: I just think it was an extraordinary collision. A collision of cultures.

MUSIC

AMY: Germaine says her community is still deeply affected by this collision. But she also says they’re not daunted.

GERMAINE: You know these changes that happened within the last couple hundred years. What is that, in terms of 12,000 years? You know that’s like the last half-hour in a day, in a 24-hour day.

AMY: There are more than 5 million American Indians and Alaskan Natives in the United States, and many of them are working to bring back bison.

GERMAINE: Restoring our relationship with bison is restoring a primary relationship...they’re a Pleistocene animal. They are our climate change adaptation strategy.

AMY: I noticed that Germaine doesn’t use words like “vanishing” or “inevitable” when she talks about her community, or the bison. She talks about strength.

GERMAINE: They've, they've been through it all. And they continue to evolve and they continue to adapt and they continue to expand. Their resilience is extraordinary. So our relationship with them I think is parallel in many ways. And now those parallel tracks are beginning to come together.

MUSIC

GERMAINE: And so all of that, all of that. That profound time depth, that profound depth of relationship with bison. All of that leaves me incredibly hopeful.

MUSIC

GERMAINE: We're resilient. We've adapted. We're still here. We’re still here. Despite it all.

MUSIC

AMY: There’s so much more to this this story. Later this season, you’ll meet other Native people who are looking at buffalo as the key to their future. And we want you to join the conversation. Find us on Facebook, or visit thresholdpodcast.org

Credits

AMY: Threshold is produced by me, Amy Martin, with help from Nick Mott, Zoe Rom, Jackson Barnett, Nora Saks and Josh Burnham. Special thanks to Michael Wright, Ross Taylor, and Michael Connor for their help on this episode. Music recorded at the Kyi-Yo Pow-Wow was used with permission of the pow-wow organizers. All of the rest of the music was by Travis Yost.

Threshold Newsletter

Sign up to learn about what we're working on and stay connected to us between seasons.